Photo by Danny Fulgencio

When you start looking, it’s amazing how many cases you find of people having heart attacks in public places. Most people who have heart attacks die. The survivors in these stories have at least one thing in common: An AED was nearby, as was someone who knew how to use it.

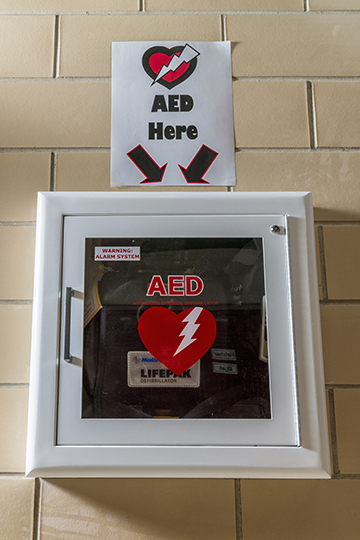

An accessible AED at school saved another life this month, this time at Reilly Elementary School in East Dallas. If you aren’t sure what an AED is or how vital they have proven, you must. Understanding what the device does and how to use it might save a life. No exaggeration—we have seen it over and over again in Dallas.

Last year, the Advocate Magazine published a piece about 13-year-old Joe Krejci’s harrowing emergency on the track at Lake Highlands Junior High. He hit the ground like a rag doll and stopped breathing, his coach told the Advocate, and if not for the teamwork and knowledge of those present, and an automated external defibrillator, AED, designed to shock an arresting heart back into rhythm, the boy would have likely died.

In February, a Jesuit football player lived, thanks to the AED waiting on the sideline.

AEDs were made mandatory in schools after a child died from cardiac arrest in 2004. An AED would have saved Fort Worth mom Laura Friend’s daughter, but none were accessible when the girl died, according to a New York Times piece. Friend lobbied for the law and also created a nonprofit to help fund the devices and training.

Dr. Jonathan Drezner, director of the Center for Sports Cardiology at the University of Washington, told the Times that, “During the academic school year 2014-15, there were 55 cases of cardiac arrest among [student athletes], and 57 percent died. I can’t believe we don’t have universal access to AEDs in schools; they should be like fire extinguishers.”

A football player about three years ago was resuscitated thanks to an AED at the stadium. One school administrator recalled at least five times the device had to be used over the years.

Two weeks prior to Joe Krejci’s near-death incident, less than a half-mile away at Wallace Elementary an AED saved a parent. Because a school nurse and several members of the school administration knew exactly what to do, they used the AED to revive the mother, who suffered no damage.

However, “The results could have been detrimental,” the victim from Wallace told the Advocate. “After 4 minutes [of unconsciousness following an attack] you can have brain damage. It could have been that, or even worse.”

The two scares prompted other schools to increase the presence of AEDs on campus.

Frighteningly, news station KSLA reported last week that there is a shortage of AEDs across the United States.

Like Drezner, the source for the aforementioned Times story, the expert in this report compared AEDs to fire extinguishers—both need to be on hand and easy for anyone to access and use.

“There’s four million [AEDs] across the United States, we need more than 30 million,” Richard Lazar, president of Readiness Systems, an AED monitoring company, told the investigative team at KSLA.

“Sudden cardiac arrest has to be treated within four or five minutes and that means an AED has to be located nearby.” The often-steep price tag is no excuse for a school district or governmental body to be unequipped with AEDs, he insists.

Host fundraisers, reallocate funds, crowdsource or whatever is necessary for AEDs, he told the station. According to the story, the national sudden cardiac arrest survival rate is at less than eight percent, a number that would increase with the increased accessibility to AEDs, experts say.

Leave A Comment