Photo by Danny Fulgencio

Located in East Dallas more than 31 years, Magdalen House has helped change women’s lives, just a few at a time in the early days, and, by extension, families going through alcoholism hell. By now, they have reached thousands,

Not a treatment or medical detox center, “we provide a form of treatment for alcoholic women,” directors (often recovering alcoholics themselves) say. “We are a supportive-educational environment … we serve women who already know they have ‘the problem,’ so we don’t directly provide assessment or clinical counseling services.”

The recovering sober staffers, alum and volunteers at Maggie’s House provide support and survival essentials—from a warm bed, nourishing food, coffee, toiletries, makeup and career-appropriate clothing to soul-mending solutions, primarily rooted in the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Maggie’s House is the first and only one of its kind in Dallas to provide this critical service, notes executive director Lisa Kroencke. You see, alcoholism is a disease that affects not only the addicted, but also their families, neighbors, strangers on the street and beyond. So this — while not as hot a topic as the opiate epidemic, which we can get to later, is kind of important to our entire city and yonder.

______

When a small group of recovering alcoholics founded Magdalen House in 1986, they took shelter, and no small amount of pride, in small home on Lovers Lane; it safely could accommodate about six women.

In 1996, funding from the Dallas Women’s Foundation allowed the evolving nonprofit to purchase the large fixer-upper located in Little Forest Hills, which founders, staffers, volunteers and temporary residents transformed into the current facility — affectionately “Maggie’s,” to most. It’s in the middle of a residential neighborhood and so close to a school that you can hear the children on the playground from the front porch, yet we’ve never heard a complaint. In fact LFH supports Maggie’s, promoting its fundraisers and events.

Treating a family disease

Reminds me of the time an all-male Oxford House, another sober living facility (albeit for those further along in recovery) opened in a northeast Dallas neighborhood. Except that time, an angry HOA member did everything in his power to boot them out. He complained about their cars. (“Do you know what a miracle it is that we can legally drive cars now?” one roommate boomed with laughter. He also complained that the house was too close to the elementary school.) This homeowner was far from first to object to sober-living houses in residential areas. A 2002 New York Times article highlights several court cases involving sober houses fighting for the right to exist in neighborhoods and cities that don’t want them.

Voices of reason in the same neighborhood, such as reader Heather, pointed out that she “would rather have sober house—with rules and standards and openness—than some of the other crazies that live nearby. Sure, they could fall off the wagon [a zero-tolerance policy, both at Oxford and Maggie’s means immediate eviction if alcohol or drug use is detected], but they are in a program … addicts live in every neighborhood, most are not trying to get better, so why don’t people quit being hateful and start seeing what is really there?”

The women of Maggie’s moved into the 1302 Redwood Cir. facility relatively quietly. They held 12-Step AA meetings and invited the community. They painted and landscaped. They vacuumed and scrubbed the floors. They created eight or so comfortable bedrooms where women could endure detoxification under close observation.

“Doctors Hospital is down the street, half mile, if they need help, because alcohol is one of the two most dangerous drugs to quit.”

People do not die from withdrawals from meth, coke or even opiates. But going cold turkey off alcohol or benzodiazepine pills can cause death.

_____

In 2009, I wrote a feature about Maggie’s. I visited six women who could have been schoolteachers, college students. One actually was a doctor — at least she had been until a DWI caused her suspension from practicing medicine. Though she started drinking relatively late in life, her 30s, the addiction quickly took hold — she lost her career, her home, her family and her freedom within a few years. On parole, Maggie’s was her last shot at freedom. She’ll likely never practice medicine again, but she could help others, if she could only get well. Women face more danger and destruction from alcoholism than men face.

Maggie’s gained a reputation—here was a place where women, with the help of other empathetic women, could begin to recover at no cost. Due to the perils of alcohol withdrawal, inpatient treatment — or round-the-clock observation of the sufferer for at least 48 hours — is vital.

And often impossible.

Inpatient treatment during this crucial detox period costs about $700-$1,000 a day. If you are insured for psychiatric care, chances are you will be required to stay at least 30 days ($15,000-$30,000); failure to do so could cause denial of any insurance coverage at all.

As folks saw the results and the extreme value of Magdalene House’s accomplishments, they stepped in and helped.

There were fundraisers and grants. Donations small and large.

But by 2010s, the house was cracking, the balcony drooping, foundation sinking (literally, although the residents were getting sober at a relatively high rate. Some returned. And again. And again even—the disease has a high rate of relapse) and founders, board members, alumni wanted a better facility and more room, executive director Lisa Kroencke says.

So they appealed to Dallas’ Board of Adjustments for “a special exception to the nonconforming use regulations to restore a nonconforming group residential facility use.” They were ready to purchase a property on Gaston, formerly home to Gaston House, for men in recovery.

But Maggie’s was denied a certificate of occupancy. Board of Adjustments member Steve Long pointed me in the direction of these meeting minutes, which outline both request and denial.

The applicant, Jackson Walker on behalf of Maggie’s, and represented by attorney Jonathan G. Vinson, did immediately appeal. Again, it was denied.

By now this “nonconforming use” crap was so irritating me that I broke down and read the Wikipedia entry; so here is what it means when it comes to zoning. Gaston House was nonconformingly using the property, and Maggie’s board members and directors believed they could do the same.

Magdalen House might not have the opportunity due to a perceived violation of the intended use of the property—the non use or “abandonment” of the property, to be precise.

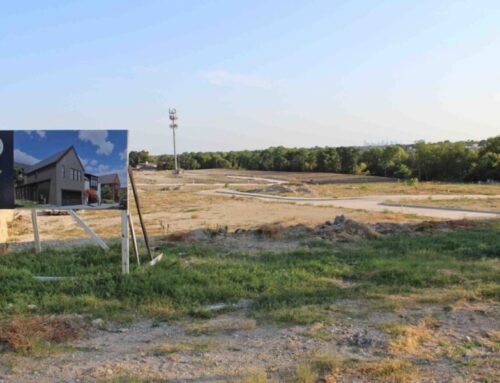

Photo by Danny Fulgencio

But Maggie’s hasn’t given up yet, and they have this Higher Power (this is an AA thing, for the unaccustomed) on their side.

Vinson, the attorney for Magdalen House, has prepared a lengthy document to be presented at the April 16 zoning board of adjustment meeting in regard to the property at 4513 Gaston, wherein he will request a special exception to the nonconforming use regulations to restore a nonconforming group residential facility use. (Meaning the women recovering at Maggie’s would be able to use it as did the men recovering at Gaston House.

It contains 186 pages, and I will read it before the meeting so we can accurately report back.

And so can you.Or you can read it to me.

Wednesday’s briefing begins at 11 at City Hall (5es) and a public hearing will be held at 1 p.m. (council chambers).

Should the day not go their way, Magdalen House can appeal to the City Council for a zoning change, Long says

Whatever happens, Magdalen House wins. The organization has gone from six ladies in a tiny dingy house to a massive yet crumbling home that would take some $100,000 to fix, Kroencke says.

The nonprofit celebrates 31 years (and heaven knows how many lives changed) June 3 at 6:30 p.m. Festivities will be held at the current facility, 1302 Redwood Circle.

Prior to that, Maggie’s members and friends will work together — service to the community being an important component of sobriety — at White Rock Lake’s Shoreline Spruceup, May 19 from 9:30-noon. Keep up with all the goings on: Facebook page.

As for the hopeful move, no one is particularly worried, primarily due to the zen practices of AA and 12 Step programs.

Says Kroencke, “We have faith.”

Leave A Comment